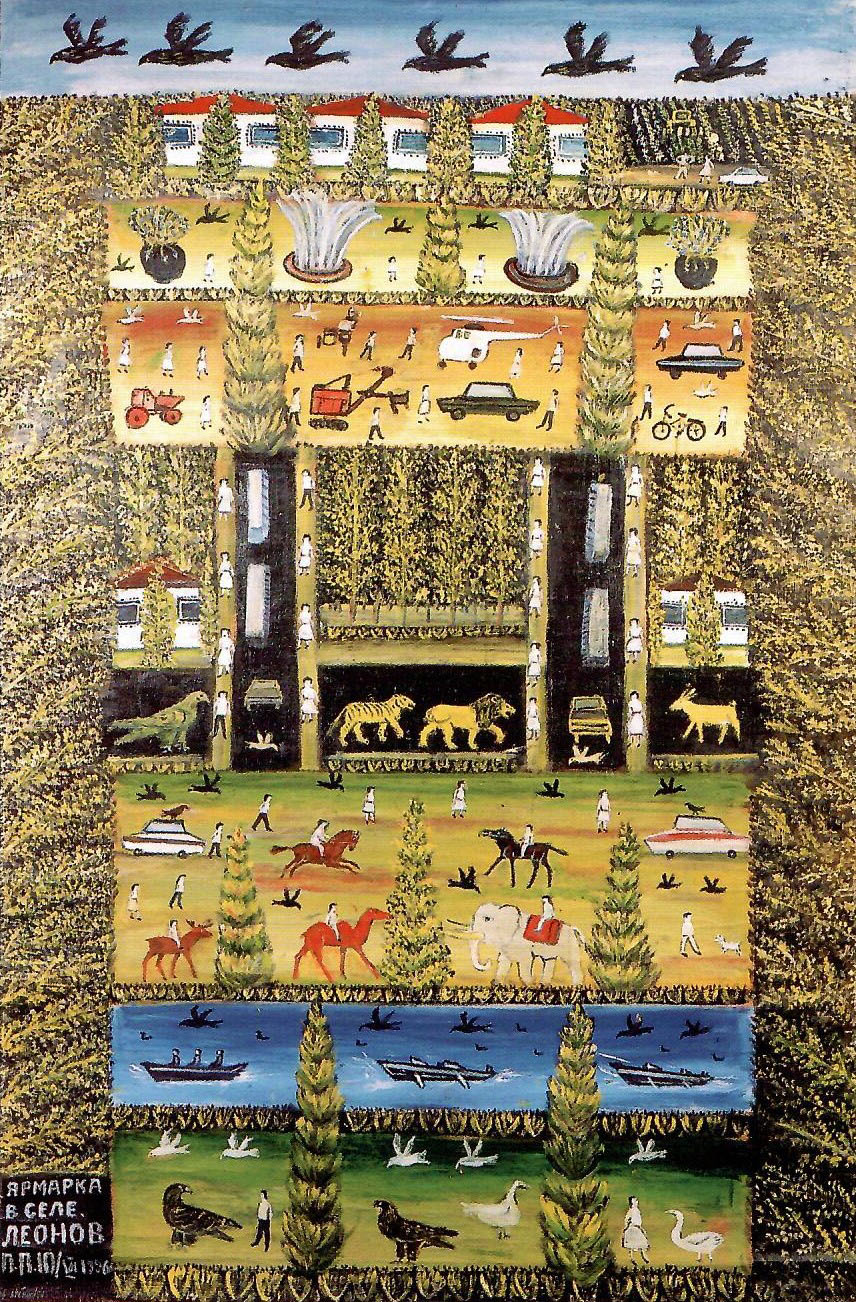

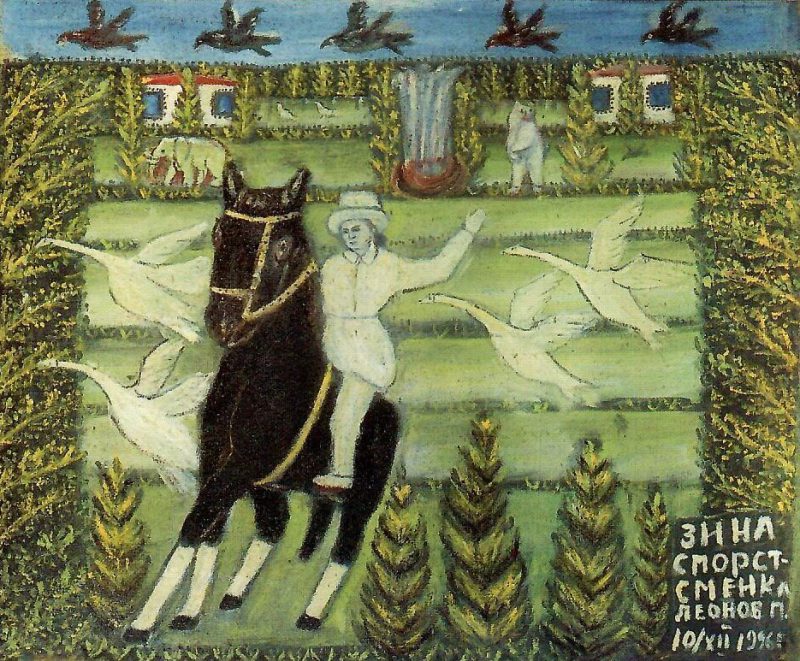

Pavel Petrovic Leonov had many lives: village librarian, cart-horse driver, miner, tin-smith, plasterer, factory worker, sign painter. Alongside these varied occupations he had one constant dream…to be an artist. Born in 1920 in the village of Volotovskoye in the Orel region, Leonov’s life mirrored many of the convulsions of the communist era. Escaping from a tyrannical father who Leonov described as “a professional alcoholic”, he left his village at the age of eighteen with five roubles in his pocket and a ticket for the train to Orel. His objective was nothing less than to participate in the building of a new society. In 1938 he was arrested for the first time. Many of Leonov’s large repertoire of skills were acquired as a prisoner of the Gulag system. As a boy Leonov taught himself to draw from a manual. In the early 1960s he attended (by correspondence) the People’s Free University in Moscow (ZNUI). There he received encouragement from the artist Mikhail Roginsky. By 1970 Leonov’s work had received serious critical attention and in the 1980s he was included in ‘The World Encyclopaedia of Naïve Art’. However, it was at this time that he also disappeared. It was not until 1990, after almost twenty years, that he was discovered living in extreme poverty in Mekhovitzi, a village in the Ivanovo region, sharing a one-room shack with his wife and teenage son. Unable to sell his paintings he had glued them to the walls as extra insulation against the severe winters. With the encouragement, among others, of Moscow-based art historians Olga Diakonitsina and Ksenia Bogemskaia, Leonov’s fortunes changed. Russian institutions like The Pushkin Museum, The Moscow Museum of Outsider Art and The Moscow Museum of Naïve Art embraced Leonov as a unique visionary artist. His work was lauded internationally, receiving the Grand Prix at INSITA in 1997. Despite his change in fortunes, his living conditions remained basic. Leonov cared little about his physical circumstances. The astonishing beauty of his work was the opposite of the life, what mattered to him was the creation and distribution of his ‘inventions’, as he called his paintings. Still invigorated by the ideals of his youth, Leonov worked at a furious pace during the 1990s, concentrating a lifetime’s insight into a decade of phenomenal productivity. In his remote village materials were hard to come by: his canvases were sometimes sackcloth, table linen or old curtains; his paints were often cheap house paint; when his brushes wore out he would resort to sticks and bristles. Aware of but far from the social and economic anarchy of the post-Perestroika period, Leonov found the space, physically and spiritually, to construct his diagrams for a better society. As arthritis gripped his hands his work began to take on a monumental scale, echoing the Soviet murals he had seen on his travels. Figures were superimposed on carpet-like backgrounds, featuring cells of idealised activity where nature and man worked in harmony together. Friends and visitors became incorporated into his work, their faces generalized, all imbued with an inner vitality. “I want to show people as the best they can be,” he said.